|

The Role of Hierarchy in Composition

Session 4: from multiplicity to subordination

4.1 General

The main idea to remember is that pictorial unity became the

main objective of painting during the 16th century. The new

vision united all the painting's shapes and textures that were

competing for attention into a unified whole and at the same

time allow them to retain their individuality.

In previous centuries individuals and groups were composed into

planes but they were disconnected and did not form any coordinated

recessional movement within the pictorial space. The creation

of overlapping planes for the foreground, middle-ground, and

background (FMB) that created a more naturalistic recessional

space.

Some paintings had been designed to be read in bands from bottom

to top (earth to heaven or heaven to earth) such the FMB was

flattened to the picture plane. Another style dictated the painting

was read in terms of overlapping bands that gave the illusion

of moving into the picture in a more life like naturalistic

fashion. This system required all human and non-human objects

in the painting to be scaled in proportional size to reflect

a more natural relationship to the real world. It is worth noting

that these changes in western art occurred in conjunction with

the alphabetization of the western world. Ideas about people

and things were no longer ranked in terms of there emotional

value but in relation to their position in the alphabet - e.g.

cows and horses were now listed before kings this was most upsetting

to kings who were also having to put up with artists wanting

to make the king more normal sized and priests who had to agree

that god could be scaled to a more life size.

So the multiplicity problem became one of placing important

figures in prime locations within the pictorial field - much

like arranging actors on a stage - but still maintaining overall

unity.

4.2 Unity through Multiplicity: We use Leonardo's Last Supper

as a sample starting point for our base style category titled

Classical. Other names have been used to identify this style:

e.g.intellectual, solid, solar - meaning daylight that exposes

every part of a scene.

The light is evenly distributed over forms that are equally

modeled. Facial expressions contribute to the emotional content.

The figures sitting behind the long table form a plane and the

figure of Christ is centralized - given slightly different clothing

colours and is isolated to a degree. All the shapes are delineated

by an edge or contour and the main shading used is known as

edge shading. There are no dark shadow areas containing objects

which require a concentrated effort to determine their identity.

To sum up: we have defined classical art as using 1) clear outlines,

2) edge shading, 3) equalized distribution of light, 4) shadow

that describes the shape of the form, 5) the ability of the

viewer to imagine a finger moving around and over every part

of the form. 6) light and shadow are completely attached to

the form in aiding its description, 7) shadow areas do not conceal

all or part of their contents, 8) there is a precision quality

to our classical approach.

4.3 Unity through subordination The 17th century gave birth

to a new vision and to illustrate this vision we will use Rembrandt's

Night Watch to illustrate our second style category titled Baroque.

It should be noted that about 200 years ago 12inches was cut

off the bottom of this painting in order for it to fit a wall

- thus compromising its original composition.

The classical style allowed everyone's facial features to be

given equal likeness in a group portrait and positions of importance

were assigned to people of importance. The new style was more

concerned with the play of light on objects than the identity

of individual people. That meant some objects would get more

light than others. Parts of those other objects may be completely

obscured by shadow and not be easily identifiable.

Light and shadow are detached from clearly defining the identity

of objects and become design features used to express overall

movement. It is a nocturnal style as opposed to a daylight style.

A style of subordination mystery and change as opposed to the

classical style of revelation exposure and timelessness.

To sum up we define baroque art as: 1) eliminating parts of

the contour such that the object is no longer completely defined

by a contour line - this results in the eye moving over the

surface of objects, 2) pictorial space is organized into recessional

planes that merge as they move into the distance, 3) light is

used to as design and not specifically to identify objects,

4) shadows partially and sometimes completelyobscure objects,

5) there is what classicists consider an imprecise sloppy quality

to our baroque approach.

We have previously studied this

under the titles :focal point, center of interest, a-chromatic

center ( maximum small area of light and dark contrast) , chromatic

center ( maximum small area of pure intense colour contrast).

All of which because of contrast attract's the eye to a shape

or the intersection of shapes.

We have also previously studied the application of different

intensities to foreground (strongest) , middle-ground (more

neutral) and back-ground, (weakest) as a means of organizing

eye movement within the pictorial space.

As you can see the word hierarchy or pyramid either of which

would be more appropriate in describing this concept.

A more detailed description which relates to our previous studies

in creating pictorial depth through the unity or pyramid approach

is provided for your review as follows:

The more you decrease the intensity of

the middle-ground plane in relation to the foreground plane

and decrease the intensity of the background plane in relation

to the middle ground plane you are creating a hierarchy of differences

between the planes. The more intense planes attract the eye

more than the less intense planes. This creates a centralized

focal area with the other areas being made subordinate or having

less eye attraction strength. All the subordinated planes work

together with the dominate plane to form a whole.

4.4 Examples:

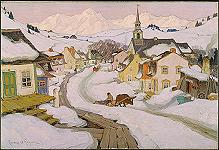

4.4.1 Example of Unity by Multiplicity (matrix)

We will view the graphic on page 10 of our reference book: "Thoughts

on the North" by Bruno Cote

I would evaluate this painting as having

a design bias towards unity by multiplicity. Normally we would

look for clarity of objects in the foreground and equal clarity

of objects in the background to determine a multiplicity style.

If we consider brush strokes as objects then the foreground

brush strokes used to describe rocks and water are as equally

clear as the brush strokes used to define tree foliage and clouds

in the middle and background.

my reasoning for classifying brush strokes as objects is that

the trees in the background are clearly represented by individual

brush strokes. A similar clarity appears in the foreground rocks

and the brush strokes used to build those rocks which in turn

are equal in clarity to the trees in the background.

My overall evaluation places this work in unity by multiplicity.

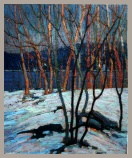

4.4.2 Example of Unity by Subordination

(pyramid)

We will view our second example by using the graphic on page

six.

This painting is an example of unity by subordination. Strong

clearly contrasted shapes in the foreground followed by less

contrasted shapes in the middle-ground, followed by even less

contrasted shapes in the background.

My overall evaluation of this work is

unity by subordination.

See following Graphic examples which

apply to this web site version of my notes:

|

|